Orwell's Happy Ending

Nineteen Eighty-Four has an optimistic hidden epilogue most readers miss

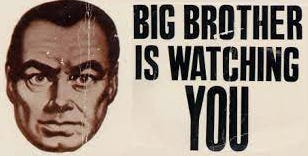

George Orwell’s masterpiece Nineteen Eighty-Four is, notoriously, something of a downer. Nobody who has read the novel can forget those haunting final lines or the emotional gut punch with which they land: “He had won the victory over himself. He loved Big Brother.” The Party has triumphed utterly: Winston Smith is irreparably broken, and our final picture of the future is, as O’Brien promised, a boot stamping on a human face forever.

Or so it seems.

But what if I told you that’s not the real end of the story? What if Orwell wrote a secret epilogue to his dystopian tale, a True Ending, hidden in plain sight at the back of every copy of the novel, which assures the reader that the totalitarian Party is toppled within at most few decades of the main story’s setting, and that freedom of thought and speech are ultimately restored?

Orwell scholars noticed this secret happy ending long ago. But if my own highly unscientific polling of my acquaintances is any indication, the vast majority of readers do not, and it seems to be rarely discussed in the high school English classes where it is frequently taught. At the time I’m writing, the novel’s Wikipedia page does not even mention it. Yet once you notice it, it’s hard to unsee—you wonder how you ever missed it.

So in honor of Orwell’s recent birthday—and to remind ourselves, in a grim era, that authoritarian regimes always collapse under their own weight eventually—let’s talk about Nineteen Eighty-Four’s secret epilogue, which can be found in the novel’s Appendix, the essay “Principles of Newspeak.”

Going by what it says on the tin, “Principles of Newspeak” is the sort of supplementary worldbuilding material that’s become a familiar staple of contemporary fantasy & speculative fiction, but was very much less so in the 1940s. It purports to explain the structure and ideological function of Oceania’s politically constructed language, Newspeak, a radically pared-down version of English that aims to render dissent impossible by defining away any vocabulary in which it could be expressed. And if we think of this as its primary function, it might seem at least a little superfluous.

The reader, after all, is not only exposed to Newspeak throughout the book, but much of Chapter V consists of a conversation between Winston Smith and his Ministry of Truth colleague Syme, hard at work on the definitive Eleventh Edition of the Newspeak Dictionary, which already includes the most important concepts elucidated in the Appendix. We learn that Newspeak aims to radically shrink the vocabulary of English, and thus to restrict the range of possible thought and expression. We learn that the great classics of literature are being slowly translated into Newspeak, harnessing their prestige for the Party while purging them of any potentially subversive meanings. The Appendix adds plenty of interesting detail, but the real meat is already there in the main text of the novel. Moreover, to the extent Orwell thought some of that extra detail was important, a good deal more could have been worked into Chapter V without unduly bogging the narrative down, or included in one of the long excerpts from the book-within-the-book, Emmanuel Goldstein’s The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism.

Nevertheless, we have clear indications Orwell regarded the Appendix as important. Nineteen Eighty-Four contains exactly one footnote, appearing just seven paragraphs into the story, and it refers the reader to the Appendix. The essay is, in effect, anchored to the main text, almost as though it were a kind of academic commentary on a historical document. In a letter to his literary agent, Leonard Moore, written in January 1949, Orwell anticipates that the American publisher may wish to cut the Appendix “which of course is not a usual thing to have in something purporting to be a novel,” but urges Moore to ensure that it is retained.

A question it might not occur to us to ask, in an era when such worldbuilding supplements are commonplace, is why Orwell chose to go about it this way at a time when it was very much “not a usual thing to have,” and might foreseeably involve some wrangling with publishers. Why insist on this rather duplicative Appendix, instead of just working as much information as the reader needs about Newspeak into the main novel? I’m going to argue that it needed to exist as a separate Appendix, because its function is not merely to elaborate on the structure of Newspeak, but to provide critical information about events in the world of the novel that occur after the action of the main story. Indeed, I believe that is its primary purpose, and the reason Orwell was so keen on its inclusion.

Let’s turn to the text of “Principles of Newspeak” itself. The first thing to note about it is that its voice is very plainly not the voice of the narrator of Nineteen Eighty-Four. The main story is told in third-person free indirect speech, anchored to Winston Smith’s perspective. The narrator, in other words, is not Winston himself, but lives in Winston’s head, and knows and feels (only) what Winston knows and feels. It is told grammatically in the past tense, but this is the kind of timeless past tense we’re accustomed to as a convention of narrative fiction. In other words, we are meant to regard the narrator as a kind of disembodied extratemporal voice, and when it uses the past tense, we are not meant to think of it as belonging to someone existing at any particular time in the future of the fictional world. When we read that it “was” a bright cold day in April, we are not supposed to wonder how long it has now been since that day in April. The voice of “Principles of Newspeak,” as I’ll elaborate on in a moment, operates very differently.

Yet, at least to my ear, the voice the Appendix is also not the voice of George Orwell. By which I mean, it is not quite written in the style or tone of Orwell the prolific essayist, columnist, and book reviewer. It is peppered with constructions like “From the foregoing account it will be seen that…” which strike me, at least, as more self-consciously formal and academic than Orwell’s “natural” essay voice. What it reads like, in short, is Orwell doing a bit—Orwell putting on the voice of an academic historian explaining a particular era. And this is precisely what Orwell is doing.

This becomes, I think, reasonably clear on a close reading of just the first paragraph of “Principles of Newspeak”:

Newspeak was the official language of Oceania and had been devised to meet the ideological needs of Ingsoc, or English Socialism. In the year 1984 there was not as yet anyone who used Newspeak as his sole means of communication, either in speech or writing.

There are already at least three things worth noting here.

First, the whole essay is written in a diegetic or “in universe” style, as though Oceania is a real place, Ingsoc a real ideology and 1984 a real time in the past (which, of course, it was not for Orwell). There is never any indication that we are talking about imaginary people or events occurring within a work of fiction.

Second, Orwell anchors the discussion precisely in time, in a way that provokes the reader to wonder “then when is it now?” as the main text, with its use of the more purely conventional “timeless” past tense, does not. He does not talk vaguely about Oceania under the rule of the party but about “the year 1984,” which is actually a little before the period the rest of the essay will be concerned with. The essay regularly refers to this period in contrast to “our own day,” as well as to the year 2050, tacitly raising the question of when the Appendix is being written in relation to these various periods.

Third, the author of this essay knows more information than Winston Smith or the narrator perched in his skull, and in particular knows about events that occur after the action of the novel. The author is certain about dates in a way that Winston and his narrator are not: Winston thinks it is probably around 1984, but cannot be sure because “it was never possible nowadays to pin down any date within a year or two.” This author is more, well, authoritative. And then there’s that beguilingly pregnant phrase “as yet.” To say that nobody in the year 1984 “as yet” used Newspeak as their primary mode of everyday speech implies that the author knows of a future time in this world, after the year 1984, when at least some people would use it daily. In just the first two sentences, and without saying it explicitly, Orwell has centered the question of where “we” are in relation to the year 1984, and made clear that the world of the narrative continues past that point, and that the author of the Appendix knows something about it.

The leading articles in the Times were written in it, but this was a tour de force which could only be carried out by a specialist. It was expected that Newspeak would have finally superseded Oldspeak (or Standard English, as we should call it) by about the year 2050. Meanwhile it gained ground steadily, all Party members tending to use Newspeak words and grammatical constructions more and more in their everyday speech.

Something very brilliant and very subtle is happening here—and Orwell repeats the trick throughout the rest of the essay. We get our first shift from a simple past tense to a counterfactual past-subjunctive. It was expected that Newspeak would have superseded Oldspeak by 2050. Orwell might have just as easily written “expected that Newspeak would supersede” and spared a word. Why doesn’t he? Because the author of the Appendix knows that this did not occur, either because the year 2050 has come and gone without Newspeak becoming the default, or because events well before that date made clear it would not happen. If I say that a person in the past believed something “would” happen by such and such a date, I leave it an open question whether their prediction came true. If I say they had believed something “would have happened” by that date, I am indicating that I know it did not.

Finally, there’s that tantalizing parenthetical: This is the first of many times that the Appendix directly references an imagined reader, as part of a “we” for whom “Oldspeak” is simply “Standard English.”

The version in use in 1984, and embodied in the Ninth and Tenth Editions of the Newspeak Dictionary, was a provisional one, and contained many superfluous words and archaic formations which were due to be suppressed later. It is with the final, perfected version, as embodied in the Eleventh Edition of the Dictionary, that we are concerned here.

Yet again, the Appendix is hammering us with evidence that it knows about events in the world of Oceania that take place after the action of the novel. As the story begins, the Tenth Edition is brand new and has only just been released to the upper echelons of the Party. The Eleventh Edition is a work in progress, which Winston’s colleague Syme is toiling away at. In the final pages, a broken Winston has been tasked to a busywork subcommittee vaguely connected to the compilation of this apparently still unpublished text. And yet here too we have a very calculated hint that things did not go as planned for the Party: The Tenth Edition contained archaic words and formations which were due to be suppressed… but which we are rather pointedly not told were suppressed later. The only reason to include the otherwise superfluous words “due to be” is to signal to the reader that this suppression did not—or at least, did not necessarily—come about.

This is a very carefully and densely constructed first paragraph—too carefully, I think, to plausibly dismiss these very consistent indications as coincidental—and the rest of the essay continues the pattern established here. On a close reading, the implication is clear: This is a historical essay, in an academic style, written from the perspective of an undefined time in the future of the universe of the novel. It demonstrates detailed knowledge of a period shortly following the action of the main text, but consistently shifts to the subjunctive when discussing events in the further future, involving the Party’s ultimate vision of a permanent totalitarian state. In that future time, it is common knowledge that the final triumph of Newspeak—and by implication the Party—did not occur as planned, and indeed, “Oldspeak” is once again standard English. Ideas of human rights and individual freedom are once again commonplaces familiar to the imagined audience that the author of this essay embraces in terms like “we” and “our”—a rhetorical tic this author character indulges in far more than Orwell did in essays written in his own real voice.

I won’t tediously go through a line-by-line exegesis of an essay you can easily read for yourself, but you’ll find the pattern continues: The author has detailed knowledge of the era immediately following the book, but gets fuzzily counterfactual whenever plans for Newspeak’s adoption in the further future are mentioned. Let’s skip to the very end of “Principles of Newspeak” to see how Orwell drives his point home. The author tells us

When Oldspeak had been once and for all superseded, the last link with the past would have been severed.

Again, not would be severed but would have been severed. The author knows that it was not. We are then told no pre-revolutionary text could be rendered into Newspeak with its meaning intact, and get this amusing line:

In practice this meant that no book written before approximately 1960 could be translated as a whole.

Of course, for Orwell and his original audience, 1960 is in the future just as much as 1984. But the implication is that by that date, we have descended far enough down the path to totalitarian collectivism that texts might be presented in Newspeak without doing too much violence to their meaning. The Appendix author then contrasts that with a “well-known passage from the Declaration of Independence”:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.

The author is not just telling us something about Newspeak, but about his own time and his own audience: That for them, the text of the Declaration is (once again) “well-known” and that its concepts of inalienable individual rights and governments founded to secure them, deriving their power from the consent of the people, are once more familiar stuff.

I do not think it is an accident that the very last paragraph of this essay again references the year 2050—indeed, “2050” is the last word of the whole Appendix. Discussing the translation of English literary and technical works into Newspeak, the author tells us that it “was not expected that they would be finished before the first or second decade of the twenty-first century. […] It was chiefly in order to allow time for the preliminary work of translation that the final adoption of Newspeak had been fixed for so late a date as 2050.” Here, too, I think the wording forces us to infer that this planned translation project was never completed. Orwell goes out of his way here not to write either that the translation work was completed by 2050, or that it is expected to be finished by 2050, but rather that this had been fixed as the completion date. The strong implication, again, is that the author knows something happened before the year 2050 to disrupt the plan. Orwell puts that number at the close of the essay by way of emphasis, because he is telling us that the Party falls before this date.

There’s one more little anomaly in the text that deserves our attention. In the middle of a technical discussion of the structure of Newspeak, we get a reference to the Ministry of Truth’s “Records Department, in which Winston Smith worked.” This is the one and only mention within the essay of a specific, individual character from the main novel, and it ought to jump out at us as a bit incongruous. In the unlikely event a reader is absorbing this essay totally apart from the main text of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the reference to Winston Smith is unhelpful, and perhaps even confusing. But for a reader who has just finished Nineteen Eighty-Four, it is quite superfluous. Unless we have very poor memories indeed, we understand well enough what the Ministry of Truth and the Records Department are, and it is neither necessary nor relevant to be reminded that Winston Smith worked there. Why is a writer as careful and parsimonious as Orwell including this otiose appositive?

The answer, I propose, is given by the threat and promise that O’Brien makes to Winston during his interrogation at the Ministry of Love:

You must stop imagining that posterity will vindicate you, Winston. Posterity will never hear of you. You will be lifted clean out from the stream of history. We shall turn you into gas and pour you into the stratosphere. Nothing will remain of you; not a name in a register, not a memory in a living brain. You will be annihilated in the past as well as in the future. You will never have existed.

Winston is there in “Principles of Newspeak” to tell us that O’Brien failed. He may have succeeded in utterly breaking his victim, but Winston has not, after all, been erased from history. Rather, Winston and his story have been heard of by posterity, to the point where an academic historian can casually (if unnecessarily) drop his name into a scholarly essay as a point of reference. For this future audience, it is the martyr who struggled in vain against the Party who is a household name, and the bureaucratic structure of the defunct Minitrue that requires explanation.

There remains an obvious question: If Orwell means to provide us an epilogue demonstrating that the Party ultimately falls within a few decades, and that humans in this world once again are well acquainted with the ideals of freedom and human rights, why is he so damned coy about it? Orwell could have instead done what, for instance, Margaret Atwood does in her own dystopian masterpiece The Handmaid’s Tale and its sequel The Testaments, providing an epilogue text clearly and explicitly marked as being written by future historians looking back on a dark, totalitarian period that has happily yielded to a more liberal and enlightened society.

I hope the answer is equally obvious to anyone who has read and loved Nineteen Eighty-Four: The book is a chilling and powerful portrait of a totalitarian world, and it ends perfectly just as it is. There is no improving on “He loved Big Brother” as a final sentence. To tack on an overt Hollywood happy ending reassuring us that everything is just dandy in the long run would have cheapened and diminished a story that, for its central character, does and must end in horror and tragedy. It would be as obscene as spray-painting a smiley face on Michelangelo’s Pietà.

And yet. We know that Orwell was not really quite as pessimistic as the reputation his magnum opus has engendered. The world of Nineteen Eighty-Four, and the philosophy espoused by O’Brien, are very clearly strongly influenced by the work of the American philosopher James Burnham, a Marxist turned vehement anticommunist, yet one who never quite got over a certain lurid admiration of absolute states. In The Managerial Revolution, Burnham envisioned a world in which (stop me if this sounds familiar) the nation states of the 20th century would coalesce into three totalitarian superstates—Europe, the Americas, and Asia—run by a technocratic oligarchy, and locked in perpetual yet restricted conflict. In The Machiavellians, he argued (stop me again if this sounds familiar) that all human political history was a chronicle of elites seeking power as an end in itself, and that any pretense to any higher altruistic, religious, or ideological purpose was an exercise in either fraudulent propaganda or (worse) self-delusion. The world of Nineteen Eighty-Four is in many respects the world Burnham predicted. The philosophy O’Brien spouts at Winston Smith (who between the regular beatings and the malnutrition is in no shape to refute it) is Burnham’s philosophy.

The influence is clear because Orwell grappled with Burnham’s work in two lengthy essays. But we also know from those essays that Orwell, even at his most pessimistic, believed that Burnham (and O’Brien) was fundamentally wrong, about both the nature of human politics and the future of the state. Orwell believed there was such a thing as human nature, and that it included an intrinsic—if not always victorious—impulse for liberty. Orwell believed that a state founded on slavery and hatred would, inevitably, either destroy itself in war or collapse under its own weight:

The huge, invincible, everlasting slave empire of which Burnham appears to dream will not be established, or, if established, will not endure, because slavery is no longer a stable basis for human society.

In short, we know that Orwell believed that a state like Oceania and its ruling Party were ineluctably doomed.

Therefore Orwell resolved this tension between the demands of his own tragic, dystopian narrative and his core political beliefs in the most ingenious way possible. He ends his story proper with the triumph of the totalitarian state and the complete destruction, body and soul, of the protagonist who struggled against it. He leaves us to stew in that unrelieved horror. But then, hidden in plain sight, he leaves us a seed of hope reflecting his own more sanguine political convictions, fully intended to be overlooked on a first pass, but clear enough to be unearthed by the attentive reader eventually. Reminding us, despite everything, that it was all right, everything was all right, the struggle was not yet finished.

Double plus good.

Fantastic stuff. You got a subscriber out of it.